Evolution has hard-wired our bodies to react to threats in a very specific way. The stress response is a survival mechanism that primes our bodies to be able to fight or flee when we are faced with a threatening and stressful situation, such as when you see a lion watching you from a distance.

Nowadays, we don’t get into positions that require us to fight off predators frequently, but we do experience many other situations that stress us out, triggering the hard-wired, automatic stress response.

The modern lifestyle in today’s world throws so many hassles at us that our ancestors never had to experience. Work, worrying about finances and paying bills, sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic, and navigating life during a pandemic… Consequently, your body treats these non-life-threatening stresses the same way as it would a threat to your life.

When you are in a state of constant stress, this evolutionary survival response is triggered repeatedly, and over time becomes extremely detrimental to your overall health.

Today, the stress response kicks in more frequently than ever and can lead to many different health issues. So what exactly happens in the body when we encounter a stressful situation?

The Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis – Explaining the stress response

The stress response consists of a series of physiological events in the body that proceeds like a domino effect almost instantaneously. The sequence of events happen before the brain’s visual centers can even fully process the event, which is why it is sometimes possible to react to a dangerous situation before you even realize what is happening.

When you experience or perceive a threat, physical or psychological, this information is sent directly to the amygdala – the emotional processing center of the brain. Your amygdala concludes that the situation is a threat, and then signals the hypothalamus – the brain’s command center – to sound off both neural and hormonal (AKA neuroendocrine) alarm signals to the rest of the body.

The hypothalamus starts by activating the sympathetic nervous system, which triggers the fight or flight response so your body can respond to the perceived threat. This happens through the sympathetic stimulation of the medulla of the adrenal glands, which releases epinephrine (AKA adrenaline) into the bloodstream.

View this post on Instagram

Epinephrine/Adrenaline Rush

This surge of epinephrine causes your heart to beat faster and your blood pressure to increase, in order to push blood to your muscles so you can better fight or escape the threat.

Stored glucose and fatty acids are released into the bloodstream to provide energy throughout the body. Your breathing rate increases in order to bring more oxygen into the body, which is sent to your muscles and to the brain to increase your level of alertness.

Meanwhile, the hypothalamus also sends off a second alarm signal to keep the sympathetic nervous system activated so that you’re able to continue to face the threat. This second alarm signal goes through what is called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

HPA Axis and Cortisol, The Stress Hormone

This second alarm signal is a hormone called corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which travels to the anterior pituitary gland where it binds to CRH receptors, triggering the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

ACTH travels through your bloodstream to reach the adrenal glands, where it binds and triggers the release of cortisol – commonly known as the stress hormone.

Cortisol keeps your body on high alert until after the dangerous situation is over with, through mobilizing energy stores and increasing blood sugar levels for a quick energy source to be used throughout the body.

Once cortisol levels start to fall, the parasympathetic nervous system (the rest-digest system) kicks in to diminish the effects of the stress response.

While the stress response is going full steam ahead, nonessential activities (such as digestion) in the body are halted. Blood is shunted away from the digestive system and other non-essential processes, towards the muscles and heart where more oxygen is needed.

Any system that doesn’t immediately serve to address the threat is shut down to conserve energy for the fight or flight response. Our bodies were designed to face stressors automatically and with intensity in order to ensure our survival.

The stress response is supposed to be self-limiting, meaning that once the event is over, the stress hormones should go back to normal levels. The diminishing of the stress hormones allows your heart rate, blood pressure, breathing rate, and blood sugar to also decrease to normal levels.

However, even in the past the dangerous situations that prompted this kind of response didn’t happen continuously throughout the day. Today, many people face constant, daily low (or high) levels of stress that keep the stress response turned on. This leads to HPA axis dysfunction, disrupting normal bodily processes, and over time can contribute to negative health outcomes.

Sympathetic Dominance – What happens when stress becomes chronic?

Chronic stress triggers the stress response over and over again. Cortisol levels remain high, making it nearly impossible for the parasympathetic nervous system to take over and fulfill its job in certain bodily processes.

When the parasympathetic nervous system is unable to fulfill its duties because you’re spending most of your life using your stress-based sympathetic nervous system – this is called sympathetic dominance.

Chronic Stress, Digestion, and Appetite

One of the roles that the parasympathetic nervous system is blocked from fulfilling due to sympathetic dominance or HPA axis dysfunction is digestion. So, it makes sense that digestive issues are a common result of chronic stress. Indigestion, IBS, malabsorption of nutrients, and many other gut health issues can be caused by – or exacerbated by – chronic stress.

These high cortisol levels also contribute to increased appetite, especially for sugar and simple carbohydrates, that can lead to overeating and weight gain, and eventually even obesity. There is a huge connection between cortisol and belly fat.

A common sign of high cortisol levels is higher levels of abdominal visceral fat, which appears as a “pot belly.” High levels of visceral fat are associated with type 2 Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome.

Chronic Stress, Inflammation, and High Blood Pressure

Chronic stress can lead to chronic inflammation, which can also keep cortisol levels elevated. Cortisol suppresses the immune system, making you more susceptible to illness and gastrointestinal issues. This can put you at risk to develop an autoimmune disease.

Another job that cortisol has is to help deliver oxygen to muscles by constricting blood vessels, which increases blood pressure. Chronic high cortisol can lead to chronic high blood pressure. This can damage blood vessels and cause blockages, paving the way for a heart attack.

HPA Axis Dysfunction and Chronic Stress

Other common issues that can arise from the overexposure to stress hormones include anxiety, depression, headaches, sleep problems, and memory issues.

Long-term stress causes HPA axis dysfunction or adrenal dysfunction. This puts you at risk for adrenal fatigue, where your adrenal glands have difficulty keeping up with the body’s constant demands to keep pumping out the hormones needed. This results in many body systems shutting down and you end up feeling completely burned out.

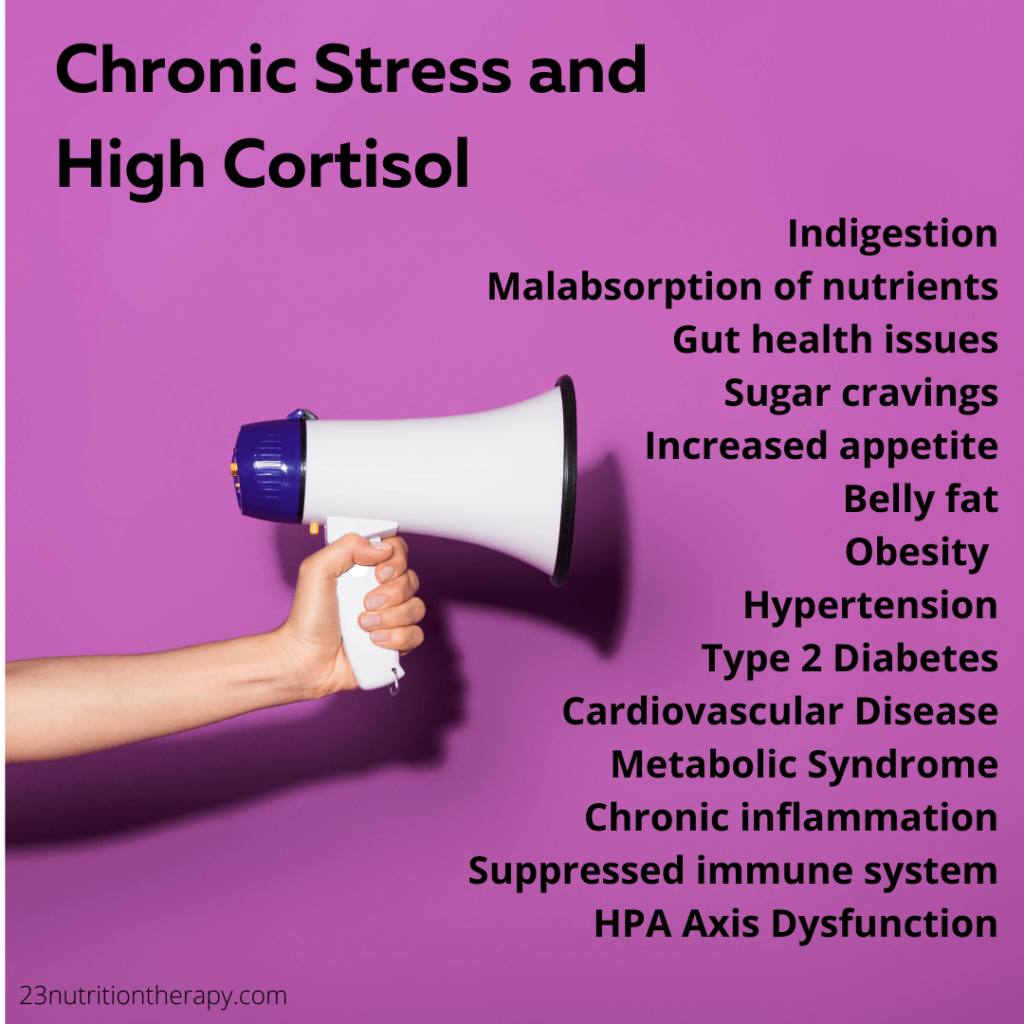

The effects of HPA Axis Dysfunction and chronic high cortisol can include:

- Indigestion

- Malabsorption of nutrients

- Gut health issues

- Sugar cravings and increased appetite

- Weight gain (especially around abdomen) and obesity

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Metabolic Syndrome

- Chronic inflammation

- Suppressed immune system

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- HPA Axis Dysfunction, Adrenal Dysfunction/Burnout/Fatigue

Low Stress Resilience – Why do some people have stronger reactions to stress?

You may have realized that some people react more strongly than others to stressful events. We all know someone who we would describe as “high-strung”. There is also the type of person who holds in all of their emotions. Finally, we may envy someone who is strangely calm when they’re under pressure.

But why is this the case? There are a few things that determine your stress resilience (your ability to react better under stress).

Genetics and Epigenetics

How we react under stress has a bit to do with genetics. People that react very strongly may have certain genes “turned on” that amp up their stress response The people who can stay relatively calm may have slightly different genes that better protect them.

Epigenetics (alterations to gene expression) in the form of gene tagging may also have an effect on how we react to stressors. For example, certain chemical compounds, like methyl groups, attached to certain genes can act as a block during gene expression. This makes it more difficult for the gene to be translated into a protein by blocking the gene, potentially altering brain signaling.

Early Life Trauma

Early life trauma also has a huge impact on how we react to stress. These traumatic events occur within the first 20 years of life while the stress systems are still developing.

These traumas can include things that aren’t even a part of your explicit memory, such as our time during infancy. Traumas can include anything that impacts you emotionally: trauma is any experience that elicits a negative emotional reaction. Early life trauma can lead to epigenetic changes to the stress systems and to the gut-brain connection.

Gut Microbiome

Another part of our physiology that early life trauma can impact is our gut microbiota. In early life, the development of the stress response is influenced by our gut microbiota. Our gut microbiome influences the brain through the metabolites and other products they produce within our digestive tracts. This is a relatively new area of research, and we’re now finding out how the bacteria that live in our gut impact our daily lives.

Three things that can negatively affect stress resilience:

- Genetics and epigenetics

- Early life trauma

- Gut microbiota or dysbiosis (imbalance in gut microbiota)

How to lower cortisol levels naturally – what you can do to tone down your stress response

Finding ways to better manage stress can lead to better health outcomes. Eliminating unnecessary stressors is always a good place to start. But some stressors in life are unavoidable and out of our control. For the stressors you can’t control, practicing stress management and using relaxation techniques are great strategies.

Sleeping well and eating healthy are both key factors that can help keep your stress levels low.

It is also important to take time for hobbies and do the things that you enjoy. This is so important for stress reduction and helps you maintain a sense of overall well being.

Staying active is another essential way to de-stress. Exercise leads to deeper breathing, which activates the parasympathetic nervous system. Muscles loosen up, relieving tension in the body. Yoga is a great way to increase mental focus while getting your muscles moving and producing a sense of calm.

Relaxation Techniques to Repair HPA Axis Dysfunction

There are quite a few self-soothing relaxation techniques that can be used to dampen your stress responses once they are activated.

These exercises include things like deep breathing, mindfulness, and meditation. These exercises can be done when you are experiencing stress to get your parasympathetic nervous system to kick in.

The exercises can also be done throughout the day in order to train your body to stay more relaxed when stressful events do occur. Practicing relaxation techniques can repair HPA axis dysfunction, making you more resilient in the face of stress.

Importance of a Lifestyle Overhaul

If you think you’re experiencing the effects of chronic stress, it is helpful to do a complete lifestyle overhaul to put you in a better position to deal with stress.

This lifestyle overhaul isn’t meant to add more stress to your life. It is best to start by adding just one of the things mentioned above. Find out what works best for you, and then slowly add on more stress-reducing activities or exercises.

Improving your resilience to stress is key to long-term health, and can help to prevent many negative health outcomes. When you’re feeling stressed out by things you cannot control, starting with one simple step can ultimately help you to gain more control over your response to stress.

Ways to lower cortisol naturally to Fix HPA Axis Dysfunction:

- Yoga

- Mindfulness

- Meditation

- Deep breathing exercises

- Lifestyle overhaul

Are your gut health issues adding additional stress in your life? Let’s tackle that together!

Schedule a meeting today to get started on the pathway to better gut health. Let me help you can gain control in your life and stress less.

Take this quiz to evaluate your stress resilience