Do you often experience abdominal pain, bloating, or acid reflux after eating? Do you reach for symptom soothers like Tums or Pepto bismol more often than you’d like to admit? Maybe you pop probiotics because you’ve heard from a friend that they help with bloating, but that isn’t working? Digestive symptoms typically signal that something has gone wrong during one of the steps to digestion.

Digestion is a very complicated process that most people don’t fully understand. There is much more going on than just food going through your mouth, reaching your stomach, and eventually coming out the other end. Each meal travels 26 feet before it ends up in the toilet! That’s 26 feet where potential problems could arise.

The digestive organs usually work in perfect coordination like a well-oiled machine. But like any machine, sometimes things can go wrong. Reaching for over-the-counter (OTC) symptom soothers is not always the best choice to address your digestive issues, especially if you are experiencing these symptoms regularly.

This blog is a quick guide to digestion and a basic explanation of all the steps to digestion. Reading this blog should help you realize that digestive issues are not usually an easy fix!

Digestion Starts in the Mouth

Digestion begins when you take a bite of your food and start to chew. The salivary glands in your mouth kick into action, infusing each bite with saliva that is filled with enzymes that kickstart the process of breaking down starches and fat. This fat digesting enzyme is only available in trace amounts for adults. In babies, it’s present in much larger amounts and helps the infant digest the fats in milk.

Chewing is imperative for multiple reasons. The first is because it breaks down your food into smooth bits that can be swallowed without choking. Chewing also helps you burst open foods like seeds that cannot be digested without being physically broken open. Many people eat way too quickly, so be mindful when you eat, and chew your food thoroughly before swallowing!

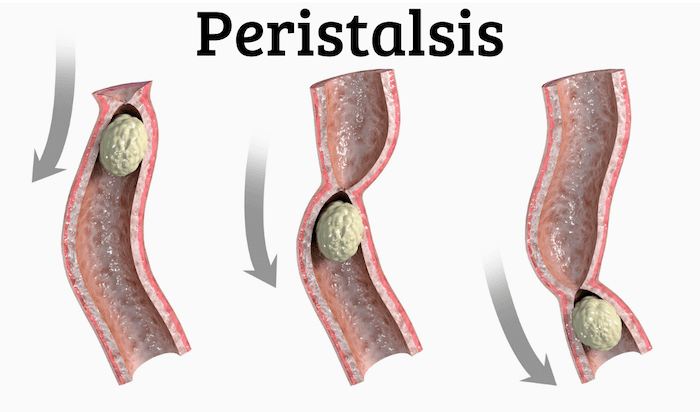

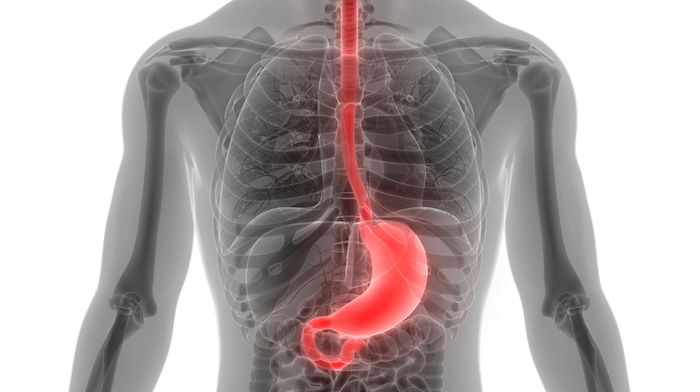

Once you swallow your food, it travels down your esophagus where wave-like movements direct it towards your stomach. These waves are referred to as peristalsis. A sphincter muscle allows entry to the stomach, and helps to prevent food from coming back up in the wrong direction. The next steps to digestion are outlined below.

The Stomach breaks down and liquefies your food

Once food exits the esophagus, it enters the stomach where it is added to stomach acid, enzymes, and fluids. Your stomach has 3 layers of thick muscles that tighten and relax, churning this mixture thoroughly until your food turns into a liquid called chyme.

There are actually a couple compartments within the stomach. When food enters the stomach, it gets stored in the top compartment shortly and then moves into the lower compartment where the churning begins.

Eventually after a lot of churning, the food becomes chyme: an acidic, mushy food paste that consists of partially digested food and gastric juices. The gastric juices contain concentrated hydrochloric acid, (HCl) water, and enzymes. Stomach acid is extremely acidic (~1.5 pH), but doesn’t damage your stomach due to the mucus produced by the walls of the stomach that protect the digestive lining. This acid will kill most bacteria that sneak their way into the stomach with your food.

At this point in digestion, the starches are partially split and proteins are uncoiled. Fats separate from the rest of the mixture and float on top of the watery, protein and carb-rich chyme. As the chyme leaves the stomach, the fat layer is the last to exit. The more fat in a meal, the slower digestion proceeds, which explains why you feel fuller longer after a fatty meal.

Food exits the stomach a little bit at a time through a valve at the bottom of the stomach called the pyloric valve. Your stomach spits out chyme into the small intestine for a few hours after your meal until it is empty.

The small intestine is responsible for nutrient absorption

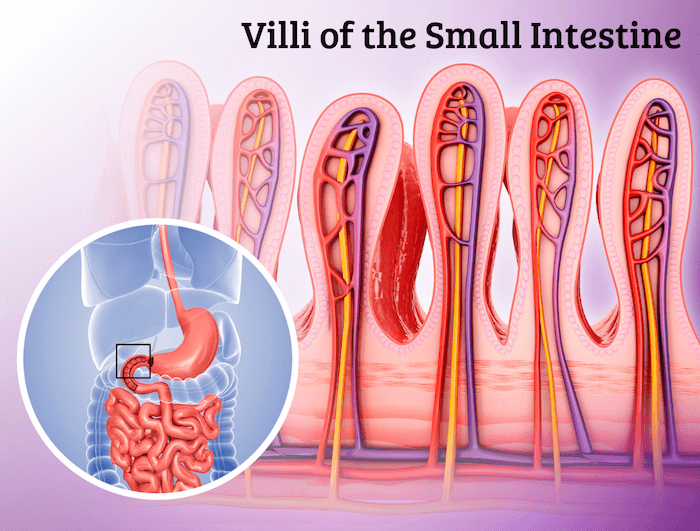

The small intestine is an incredibly long and winding organ where the majority of nutrient absorption occurs. There is so much surface area on the walls of the small intestine that if it were laid out flat, it would cover 1/3 of a football field!

This hugely important organ receives and secretes enzymes in response to food to help break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in preparation for absorption. You may be able to guess that the role the small intestine plays is actually one of the most important steps to digestion, and you would be correct. Each step is extremely important, but nutrient absorption is essential to life.

The cells along the walls lining the small intestine have finger-like projections called villi that pick up vitamins, minerals, and broken down nutrients once they’re small enough to absorb. Each villus then directs these nutrients into your bloodstream or into your lymph.

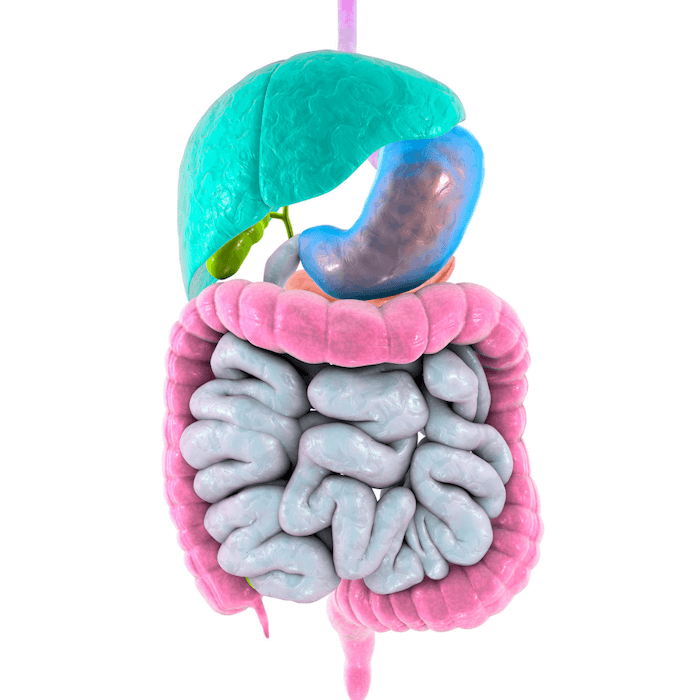

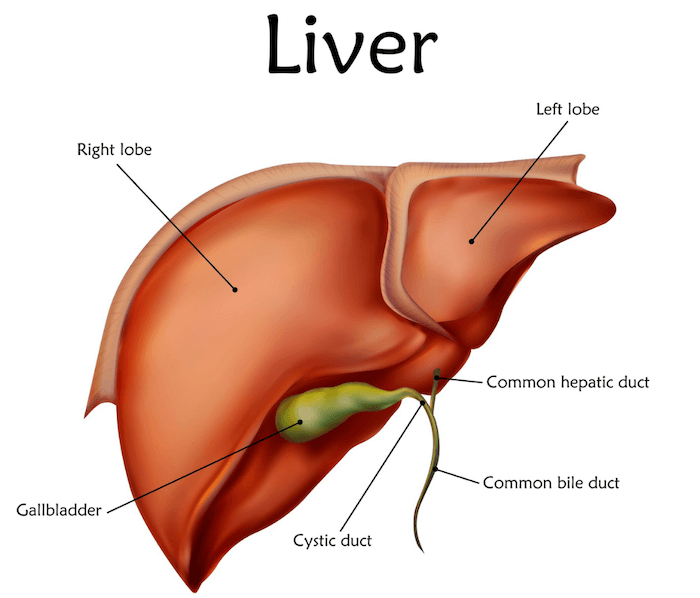

The liver and gallbladder are in charge of bile production and storage

Your liver has many functions, but did you know it plays a role in digestion? The liver produces bile, which helps digest fats. The liver sends bile over to the gallbladder for storage, where it remains until needed in the small intestine. Once the small intestine is in need of bile, hormone messengers signal the gallbladder to contract and squirt bile through the bile duct into the small intestine.

Bile is an emulsifier. What this means is that it causes the separated fat layer to become suspended within the watery chyme. This leads to more fat being exposed to fat-digesting enzymes for optimal absorption. Most bile gets reabsorbed and reused, but some may exit the body with the feces at the end of all the steps to digestion.

It is indeed possible to live without a gallbladder, because the liver will continue to produce bile. But instead of the bile getting stored somewhere, it is delivered directly into the small intestine through a different duct. If you have had gallbladder removal surgery (and even if you haven’t), you may need some supplemental bile and enzyme support.

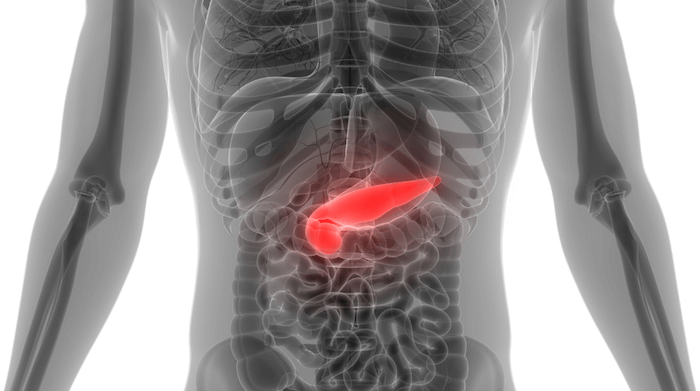

Your pancreas secretes digestive enzymes

Your pancreas is in charge of making digestive enzymes that help break down macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) into smaller and smaller pieces until the nutrients are small enough to be absorbed.

The job of the pancreas is to release pancreatic juices containing these digestive enzymes into the small intestine. Pancreatic juices also include alkaline bicarbonate, which neutralizes the stomach acid that enters the small intestine with chyme. The pancreas plays an essential role in digestion because the small intestine cannot play its role in nutrient absorption without these digestive enzymes.

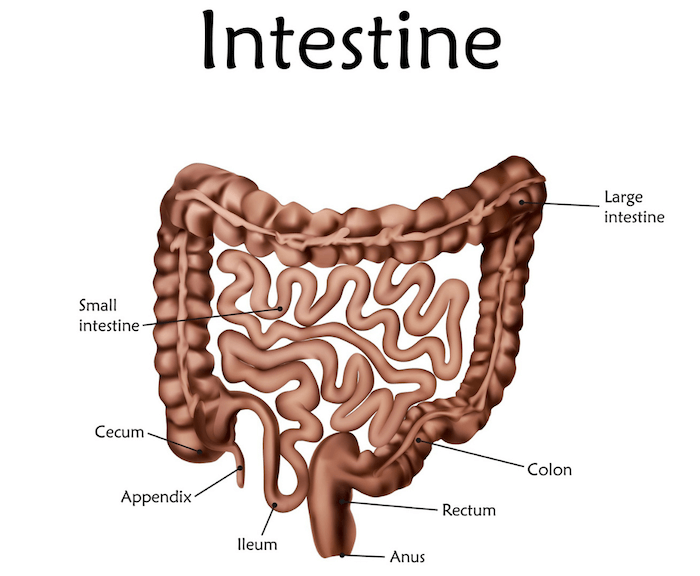

One type of nutrient that doesn’t get absorbed in the small intestine is fiber. So, fiber will move along into the large intestine for the next steps to digestion.

Stool is formed in the large intestine

Once the remnants of your food enter the large intestine (colon), digestion and absorption are mostly complete. Essentially all of the carbs, fat, and protein have been digested and absorbed at this point.

The colon absorbs any leftover minerals and reabsorbs water that was donated by other digestive organs earlier in the digestive process. What is left behind is a paste containing water, indigestible fiber, dead bacteria, and any other undigested materials: this is what makes up your feces. The longer stool sits in the colon, the more water is extracted and the harder your feces become, leading to constipation.

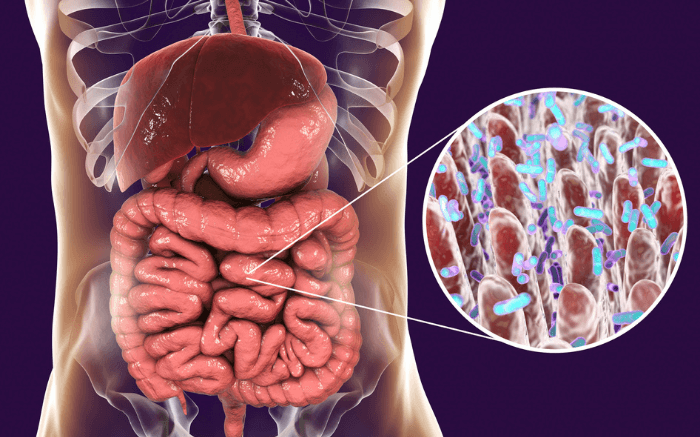

A lesser-known organ: the gut microbiota

Our colon contains about 100 trillion beneficial microbes. They outnumber human cells by about 10 times! In a way, the gut microbiota can be considered its own organ. For example, humans don’t create enzymes that allow us to digest fibers, so this is where the gut bacteria come in handy.

Gut bacteria are able to ferment and break down fibers for us. They salvage nutrients for us that we wouldn’t necessarily have access to otherwise. They turn fibers into short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate that benefit us in many ways. For example, SCFAs can give energy to colon cells, can protect against inflammation, and can even promote brain health.

Our gut microbiota also break down and help recycle the components of bile. They can even produce some vitamins for us, but not in amounts large enough to meet our body’s needs. So it is still very important to make sure you have a balanced diet based on a variety of foods to ensure you are consuming enough micronutrients.

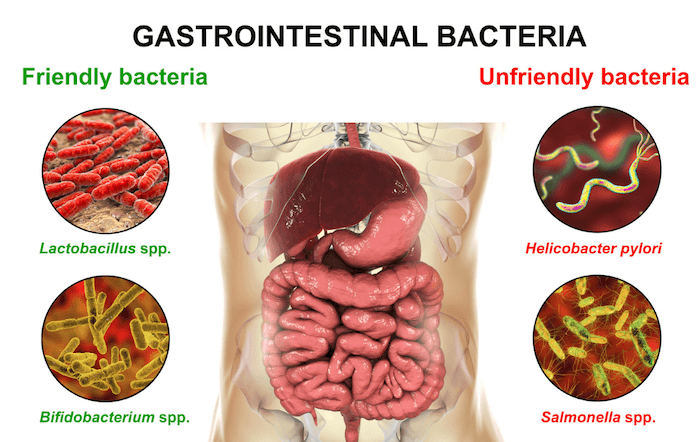

Our gut microbiota can also be thrown out of balance, in a state called dysbiosis. Dysbiosis occurs when you have a higher proportion of unfriendly bacteria compared to friendly bacteria. This can lead to many other health complications. A comprehensive stool test can be used to determine whether or not you are experiencing dysbiosis or have a balanced microbiome.

Research about the gut microbiota is booming. There is still so much that we don’t understand, but we are just now realizing the impact these bacteria have on our lives.

Potential root causes of digestive dysfunction

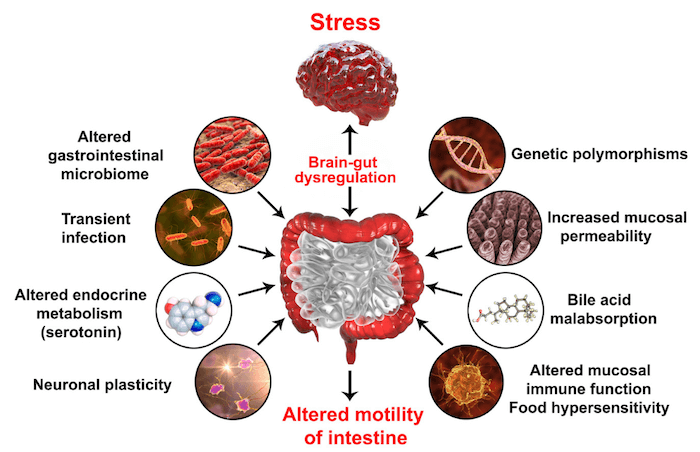

So now you should understand a little bit about the complex interrelation between the digestive organs. There are many points along the way where problems could arise.

Here are some examples of potential root causes that can lead to various digestive and absorption issues:

- Not fully chewing your food

- Sphincter muscle dysfunction between stomach and esophagus

- Small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) due to bacteria leaking from the mouth or relocating from the large intestine

- Low stomach acid production

- Insufficient bile flow

- Low production of pancreatic enzymes

- Motility dysfunction of the small or large intestine

- Dysbiosis of gut microbiota

- Chronic stress

OTC medications simply mask your symptoms but they don’t address the root cause. This is like putting a band-aid on your symptoms, only providing temporary relief. Diving deep into the steps to digestion to really understand your digestive function, and finding the issue your symptoms stem from is often the only way to get rid of uncomfortable symptoms for good!

Do you need some help figuring out the root cause that your digestive issues are stemming from?

Schedule your appointment today to get your digestive system back in check!

Interested in learning more about digestive health? Read our other blog, “Heal Your Gut with 5 Simple Lifestyle Changes” to learn more about what you can get started on doing today!